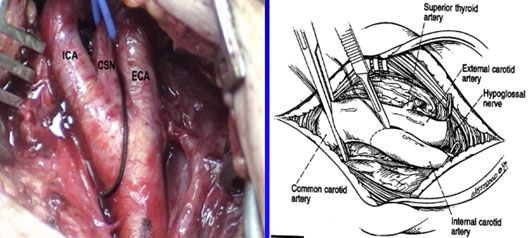

Anatomic Landmarks

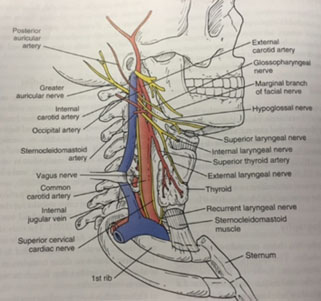

The right common carotid artery arises from a bifurcation of the brachiocephalic trunk (the right subclavian artery is the other branch). This bifurcation occurs roughly at the level of the right sternoclavicular joint.

The left common carotid artery branches directly from the arch of aorta. The left and right common carotid arteries ascend up the neck, lateral to the trachea and the esophagus. They do not give off any branches in the neck.

At the level of the superior margin of the thyroid cartilage (C4), the carotid arteries split into the external and internal carotid arteries. This bifurcation occurs in an anatomical area known as the carotid triangle.

The common carotid and internal carotid are slightly dilated here, this area is known as the carotid sinus, and is important in detecting and regulating blood pressure.

- An important consideration for carotid exposure is the anatomy that you are dealing with, in particular, the locations and aberrations of the cranial nerves.

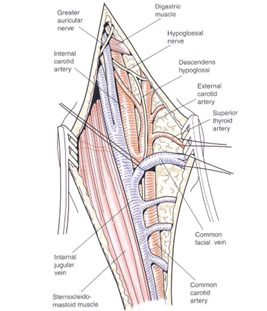

- One important consideration is that when you start high, you should be sure you are looking for the hypoglossal nerve and the glossopharyngeal nerve if you are up above or near the digastric.

Equipment

TBD

Positioning

The patient is positioned with the neck extended and the head turned away from the side of the surgery.

The incision is made along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Exposure

The exposure of a carotid artery is considered a high exposure, somewhere around the C2 level. I would argue that it is very difficult, even with CT or MRIs, to corroborate exactly where the carotid bifurcation is.

If you have running plaque that goes up above C2, that would be something that you would need proximal and more cephalad exposure. Carotid body tumors, especially Shamblin 2 and 3, are the ones that may have some difficulty more cephalad, especially around the cranial nerves.

To obtain a cephalad exposure to access the internal carotid artery, there are a few steps, each giving about 2 cm of cephalad exposure as you go.

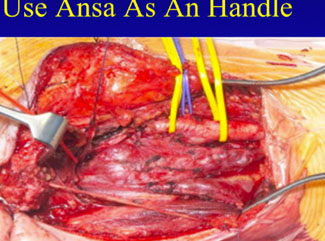

- Free up the hypoglossal by transecting the ansa cervicalis. Some people like to leave it as a little tag and bring it up and use it as a handle in order to move it out of the way. Suture ligate the “sling” artery, which branches off of the ophthalmic that comes up. Clips will not work, as they fall off and cause bleeding. This allows free transport of the hypoglossal medially underneath the jaw in order to get to the cephalad exposure of the internal carotid. Medial and cephalad retraction it takes it out of the way and minimizes the potential complications.

- If more exposure is needed, transect the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. This provides an additional 2 cm of cephalad exposure of the internal carotid artery and allows you to get higher up toward the base of the skull. Suture ligate both sides to minimize the amount of bleeding and transect it. Often this can be done with a bovie, but care should be taken to inspect the site to ensure that there is no bleeding from the posterior belly of the muscle.

- Subluxation of the jaw must be performed prior to surgery. Nasotracheal intubation is required. The jaw is thrust forward. The jaw is subluxed (not dislocated) in order to move it anterior to obtain better exposure of the internal carotid artery. Exposure is anterior to the ear (with an ENT surgeon). This raises the angle because you are moving the jaw anterior, not breaking the ligaments, dislocating it. This provides the angle between the jaw and the base of the skull.

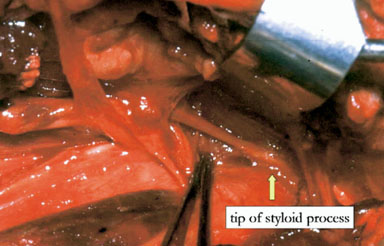

- The styloid process is a long, sharp posterior based structure that can sometimes impede the internal carotid artery. A rongeur can be used to remove, which can provide another 1 cm of access, especially in patients who have some impingement on their carotid.

- The mandibular split can provide another 1 to 1.5 cm of access. You must avoid the nerve. An ENT is needed because it needs to be plated afterward. This is not recommended unless absolutely necessary.

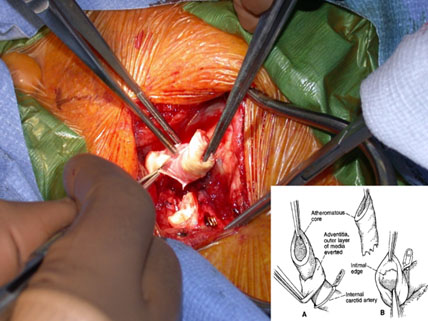

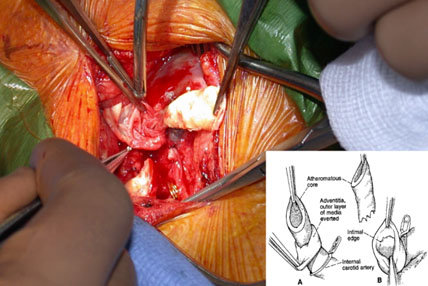

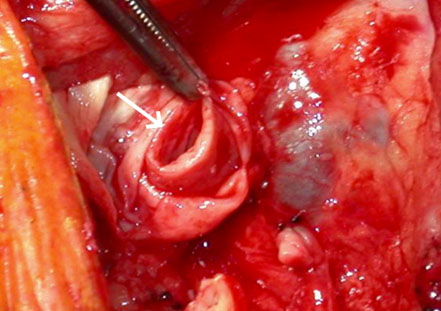

Eversion Technique

The carotid cut in half.

This allows you to pull this outside of the body as it is being dissected.

This also elongates the carotid so that you can access the distal point of the disease.

One of the reasons you need to get expansive exposure, especially on the proximal carotid, is that we are used to looking at things straight up and down. With this technique, we look down the pipe a lot, so we are a little more comfortable being cornered in a bit, and this may be one of the reasons we haven’t had to do it.

Complications

- The risk of perioperative stroke is ≤ 1.5% in expert series.

- The risk of a clinically significant cranial nerve injury is similarly small in experienced hands and includes:

- Injury to the hypoglossal nerve with tongue deviation toward the operative side.

- Injury to the vagus nerve or a nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve (which may result in ipsilateral vocal cord paralysis).

- Superior laryngeal nerve injury (which may result in difficulty speaking at high pitch).

- A retraction injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve (which may result in a lower facial droop).

- Glossopharyngeal nerve injury (a concern in exposures approaching the skull base).

- Spinal accessory nerve injury (a risk only if dissection is not conducted anterior to the internal jugular vein).

- Other complications include myocardial infarction, postoperative bleeding requiring reexploration, wound infection, local sensory loss, and restenosis.

- It should be emphasized that regular postoperative surveillance by duplex ultrasound is required to monitor for restenosis.

Pearls

- Know your anatomy, especially the nerves. Make sure as you go down, you look for the nerves not just arteries, because that is where you cause your problems.

- Adjunctive procedures may be helpful, but these need to be preoperatively decided. Good preoperative imaging will help you analyze exactly where you are and what you need to do at the time.

- Use your ENT and neurosurgery colleagues to help you.

- Know potential complications.

- Consider alternative techniques (endovascular and open), especially for occlusive disease where you don’t need to go to the cephalad carotid as much.

References

- Naylor AR, Moir A: An aid to accessing the distal internal carotid artery. J Vasc Surg 2009:29;1345-1347.

- Nelson SR, Schow SR, Stein SM, Talkington CM: Enhanced exposure for the extracranial ICA. Ann Vasc Surg. 1992:6;467-472.